Photograph by Rafico Ruiz

Viewing International Grenfell Association found footage at the Labrador Institute. Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador, 2011.

The Grenfell Mission’s enactment of infrastructural mediation was both a settler colonial project and an everyday homiletic practice that would reshape fisherfolk lives, their North Atlantic extractive environment, and, in hindsight, relationships to the affective and practical management of a colonial order that persists today.

This places equal emphasis on the emergent, durational character of infrastructural mediation that the book tracks across the Grenfell Mission story—it also makes my telling of the story into just such a media and historiographical event.

Like the promise of extraction, this story is to be made and unmade through the Grenfell Mission archives, “generative substances” for epistemologies that pursue knowledge forms that privilege settler accountability and the lived locales across northern Newfoundland and Labrador that are a testament to “the way it was.”

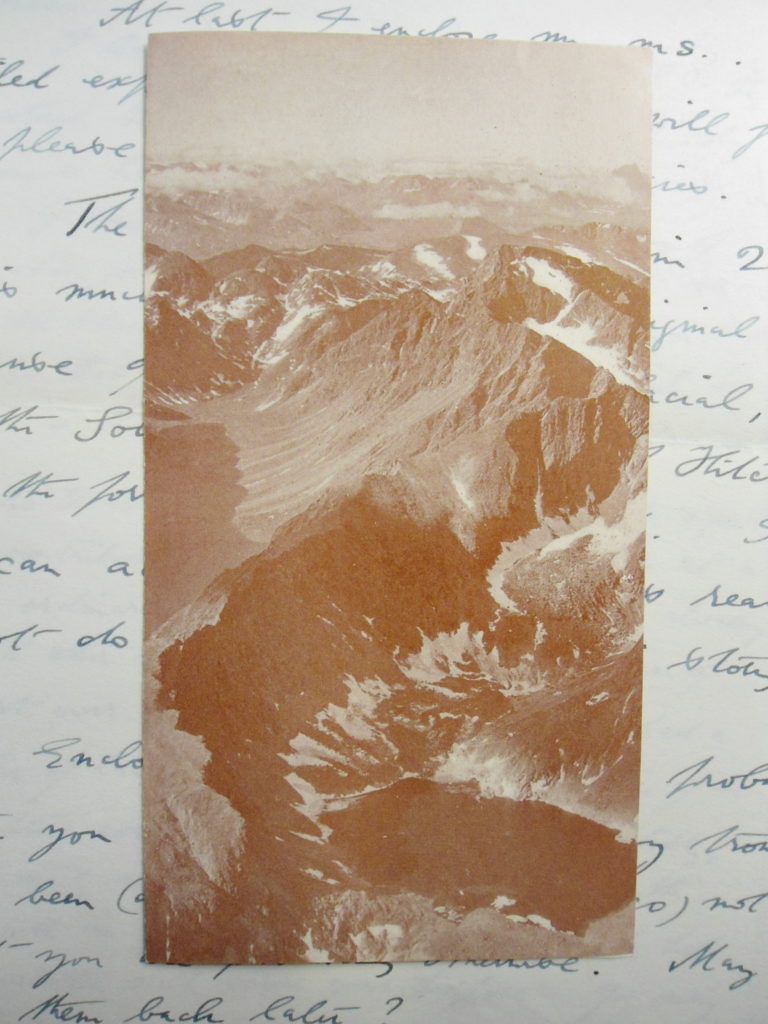

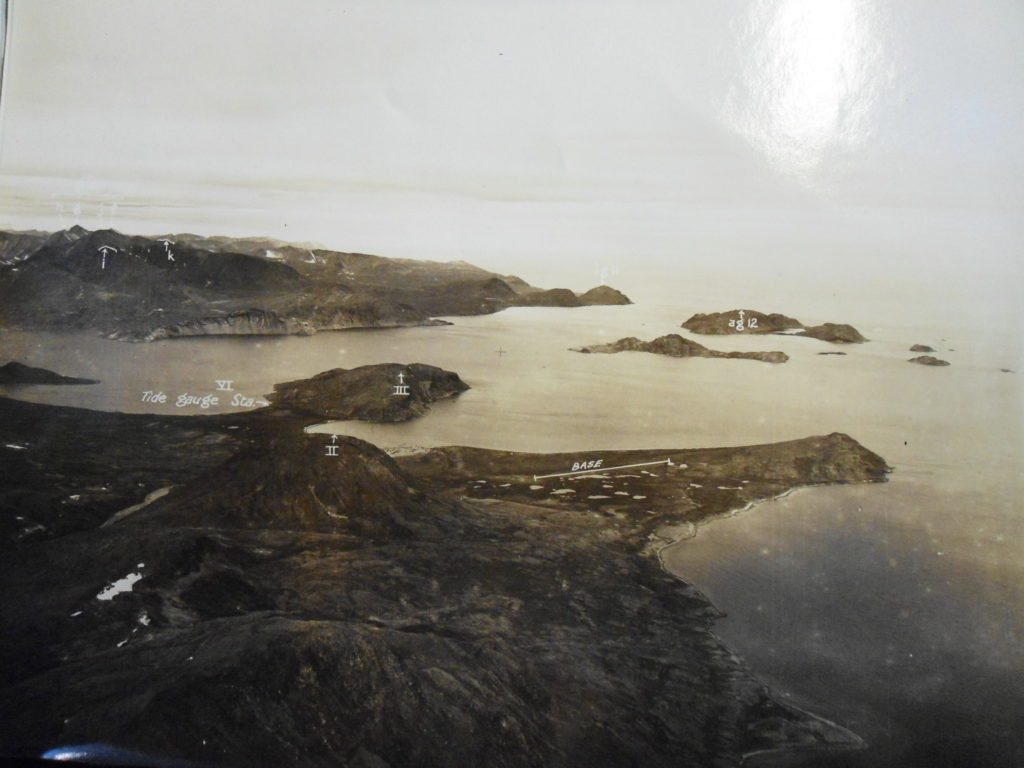

Oblique aerial photograph of the North Coast of Labrador included as part of O. M. Miller’s ground survey report. Box 100, folder 2187, Alexander Forbes Papers, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Center for the History of Medicine, Harvard Medical Library.

This is an infrastructural trail that leads at once back in time to the colonial fishery and into an unknown future around North Atlantic extractive frontier making.

I take inspiration from Harold Innis’s emphasis on the structural, political, and economic conditions of resource frontiers, and I aim to follow this line of inquiry throughout the book in order to examine the experiential modalities that underpin resource frontiers, that is, how the Grenfell Mission relied on particular processes of infrastructural mediation to shape the subjectivities of these North Atlantic settler colonists.

Slow disturbance mediation is an effort to adopt ecology’s capacity to foreground processes of change that are grounded in vital and symbiotic conceptions of human and nonhuman life. It is a reminder that the forms of mediation registered by an environmentally inflected medium such as a resource frontier are accretive, waves of disturbance that bind together settler and shore.

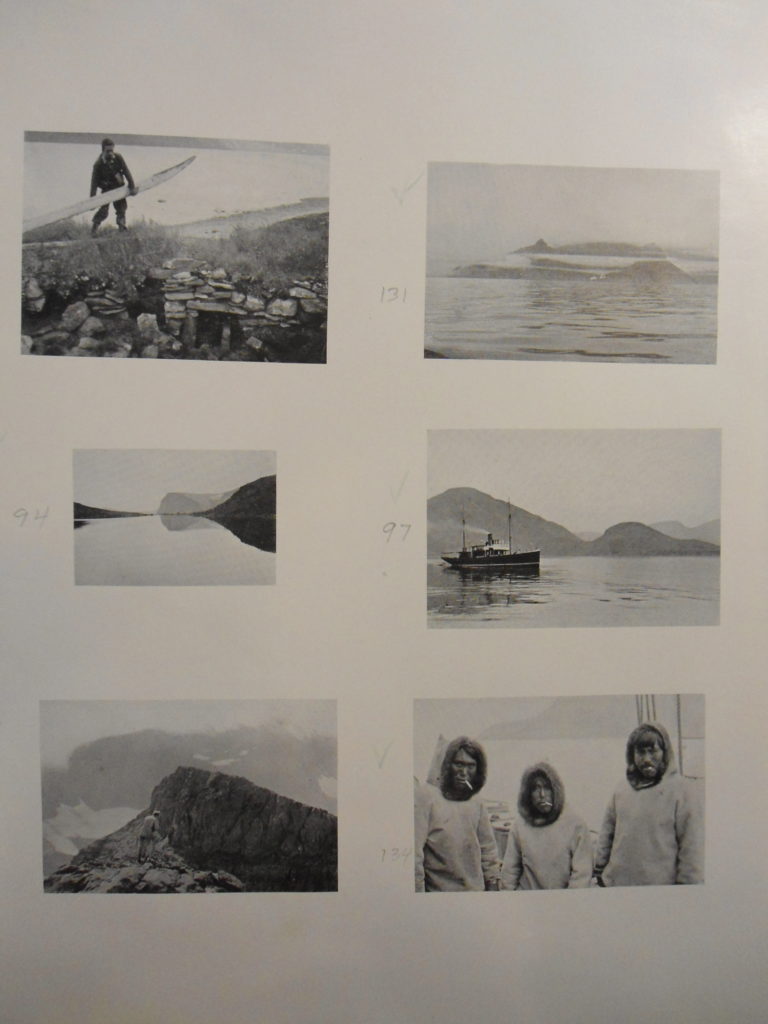

Publishers proofs of images to appear in Northernmost Labrador Mapped from the Air. Box 45, folder 1552, Re: “Northernmost Labrador Mapped from the Air,” 1938 (no. 17 of 23 folders), Alexander Forbes Papers, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Center for the History of Medicine, Harvard Medical Library.

Each chapter examines how an infrastructural zone came into being through the incremental reduction of infrastructural difference the mission undertook through its elaborate practices of reform—infrastructural difference could be made to account for the material lack that the “neglected” settler fisherfolk experienced.

In tracing how the Grenfell Mission put to work varied practices of reform in the service of their project of infrastructural mediation, of reshaping this particular colonial resource frontier, I created a broad field of inquiry—fieldwork, archival practices, visual methods—that could attend to questions of duration, affect, infrastructure, and the settler colonial project.

“Infrastructure is by definition future oriented,” Deb Cowen writes; “it is assembled in the service of worlds to come. Infrastructure demands a focus on what underpins and enables formations of power and the material organization of everyday life.”

Photograph by Rafico Ruiz

Models in Francis Patey’s basement workshop. St. Anthony, Newfoundland and Labrador, 2011.

Photograph by Rafico Ruiz

Charles S. Curtis Memorial Hospital outbuilding, St. Anthony, Newfoundland and Labrador, 2011.

The Grenfell Mission staked its claim in remaking and projecting this particular North Atlantic colonial world. Their infrastructural work was a case of both imagining alternative infrastructures to those of the prevailing and usually inequitable imperial and capitalist resource economies while also making that work complicit in the maintenance of a settler colonial project.

Resource frontiers give rise to a horizon of infrastructural worlds—settler, colonial, and settled.

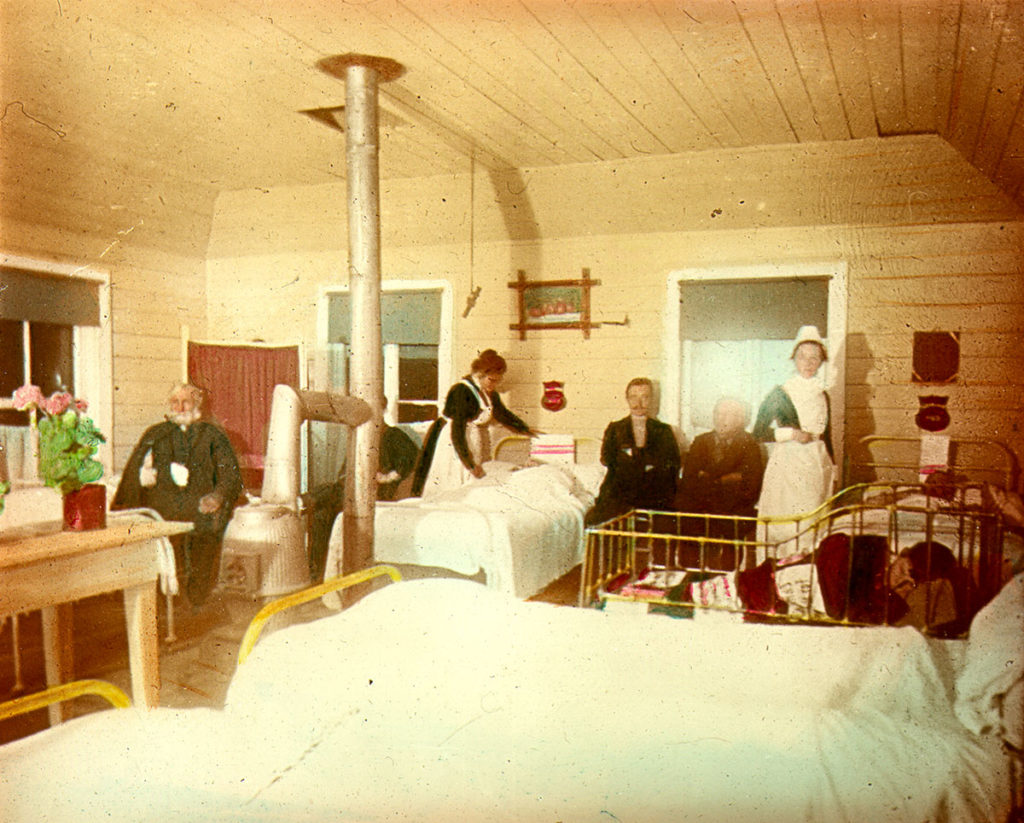

Collection of IGA magic lantern slides from the 1920s, Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador, “IGA Magic Lantern Shows,” The Rooms,.